For decades, the Kennedy Center has come to symbolize freedom of expression, representation and creativity in the performing arts.

Since the Kennedy Center opened its doors in 1971 as both an arts complex and a living memorial to President John F. Kennedy, performers from all over the world in dance, theater, music and more, have graced its stages. As a partially federally-funded institution, it has had historically bipartisan support and no sitting president has ever served as its chairman. Until now, that is.

President Donald Trump was elected chairman by a board that excluded the 18 Democratic appointees who were purged by the president after he announced an aggressive plan to reshape the center’s programming, telling reporters last month that “we’re going to make sure that it’s good and it’s not going to be woke. There’s no more woke in this country.”

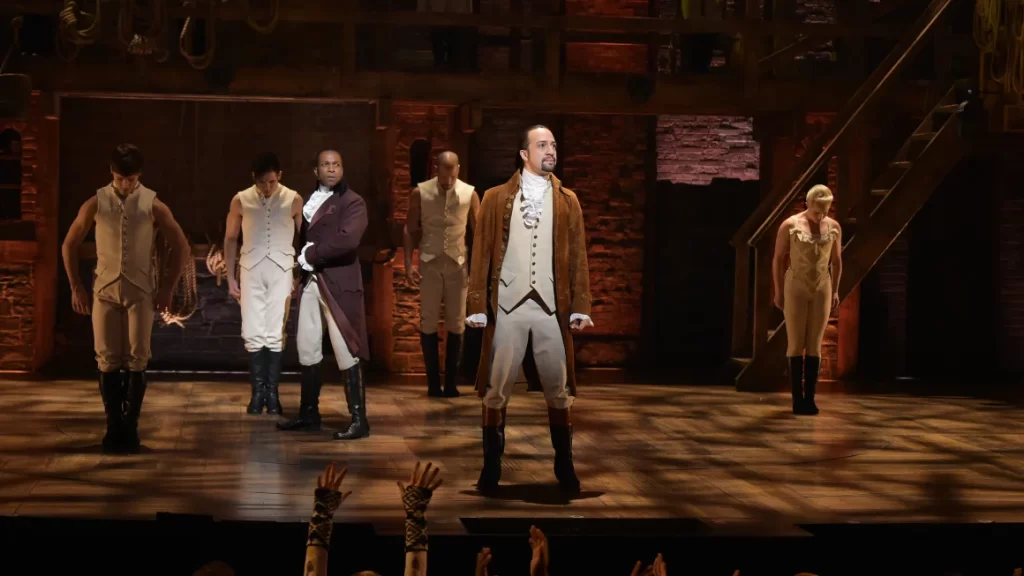

The move prompted Jeffrey Seller, producer of the hit musical “Hamilton,” to cancel the show’s upcoming run through 2026 at the Kennedy Center, writing in a statement posted on Wednesday to the musical’s X page that Trump’s “purge” of Kennedy Center staff and events “flies in the face of everything this national center represents.”

“We cannot presently support an institution that has been forced by external forces to betray its mission as a national cultural center that fosters the free expression of art in The United States of America,” Seller added.

Artists including Issa Rae, Shonda Rhimes and Ben Folds, have also resigned from their leadership roles or canceled events at the space, while the center has canceled performances including the children’s musical “Finn.” “Hamilton” backing out, however, marks one of the highest profile shows to remove itself while directly citing Trump’s sweeping changes.

Deborah Rutter, former President of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, speaking onstage during the 2023 Annual Global Leadership Awards at The Kennedy Center in Washington, DC. Leigh Vogel/Getty Images

Deborah Rutter, the now-former president of the Kennedy Center who was replaced last month by Richard Grenell, a longtime Trump confidant, began her tenure in 2014 with the mandate to ensure that the center represented all of America.

She stopped short of predicting what may happen with Trump at the helm, but told CNN’s Jake Tapper in a recent interview, “I do know that in my career lifting up and supporting artists, they need to have a great environment for work. They need to feel safe, they need to feel welcome.”

A rich history

The idea for a national cultural center was initially that of President Dwight Eisenhower, a Republican who in the mid-50s recognized a desire to establish a center for the arts in America like those he saw in Europe.

In 1958, Eisenhower signed the National Cultural Center Act, marking the first time in history the government helped finance a structure dedicated to the arts.

President John F. Kennedy, left, looks at a model of the Kennedy Center on October 8, 1963 in Washington, DC. National Archives/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

President Kennedy continued Eisenhower’s efforts when his presidency began in 1961, viewing performing arts as essential to the health of the country.

“I see little of more importance to the future of our country and our civilization than full recognition of the place of the artist,” Kennedy said during a 1962 fundraising event for the cultural center.

After his assassination in 1963, the National Cultural Center became known as the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in his memory. Because the institution is a living memorial, it is partially funded by the government to maintain and operate the building but relies on private donations and ticket sales to fund its programming.

President Lyndon B. Johnson first broke ground at the center’s construction site on December 3, 1964, just one year after Kennedy’s death. What eventually arose was a white marble Edward Durell Stone-designed structure that sits atop the shore of the Potomac.

“It’s a place where you can come see new art and new ideas and feel a sense of community that art fosters,” Rose Kennedy Schlossberg, Kennedy’s granddaughter, told “CBS This Morning” in 2022. “I think that’s a really fitting tribute to my grandfather.”

A memorial bust of former US President John F. Kennedy is seen as patrons attending the Washington National Opera walk in the lobby of the John F. Kennedy Center for the performing arts. Paul J. Richards/AFP via Getty Images

Michelle Mulitz, daughter of philanthropists and financial supporters of the Kennedy Center Shelley and the late Thomas Mulitz, told CNN that her parents always encouraged her and her siblings to engage with the arts. The Kennedy Center is place where Mulitz felt free to experience and express that.

“They went to social things all the time and the arts were always part of that,” she said. “It was something they instilled in us. It was always important to them that we saw everything.”

Mulitz is herself an artist, having worked as an actress and a designer, and now shares two children with her husband Ben Feldman, who is also an actor. As both observer and a practitioner of the arts, she is hopeful but apprehensive about the future of the Kennedy Center under its new administration.

“I think you can’t underestimate the artists community and the creative community and the numbers and the strength that they have,” she said. “I think the culture is going to change.”

Artistic expression

The 1971 opening gala of the Kennedy Center was punctuated with a production of “Mass” by famed conductor Leonard Bernstein, featuring several choruses, Alvin Ailey’s dance company, a marching band and a rock band.

Then-president Richard Nixon declined attending the opening gala performance of “Mass.” At the time, it was seen as a controversial production amid the Vietnam War and other socio-political strife given its anti-establishment and anti-war messaging. Still, the Jacqueline Kennedy Onasiss-commissioned production went on to open the center in honor of her late husband.

The National Symphony Orchestra performing at the Kennedy Center in Washington, DC in February 2024. Craig Hudson for The Washington Post via Getty Images

For decades thereafter, the Kennedy Center has put on tens of thousands of performances in all areas of the performing arts including ballet, opera, theater, comedy and dance, and is the home of the National Symphony Orchestra.

The Kennedy Center today is perhaps best known for hosting the Kennedy Center Honors ceremony, which recognizes the lifelong achievements of accomplished artists of all backgrounds. Everyone from Paul McCartney to Lucille Ball to Alvin Ailey, among many others, have been honored at the annual ceremony since 1978.

Past presidents of both parties have often appeared at the Kennedy Center Honors, putting politics aside for the night and engaging in the moments of levity. That changed during Trump’s first term, when he skipped the 2017 ceremony, saying at the time he did not want to be a “political distraction.”

(Center left) Former First Lady Jill Biden, Former President Joe Biden, Former Vice-President Kamala Harris and Former Second Gentleman Doug Emhoff at the 2024 Kennedy Center Honors. Chris Kleponis/AFP via Getty Images

Throughout the decades, the Kennedy Center has been host to several festivals celebrating world art including 2009’s “Arabesque: Arts of the Arab World” festival, which marked an unprecedented exploration of Arab culture.

“I believe that peace comes from understanding,” then-Kennedy Center president Michael Kaiser told PBS in an interview about the festival. “If we know more about other people and have a rounder view of them and a more educated view of other people, then we can start to make peace.”

Under Rutter’s leadership, she made it a point to practice Kaiser’s sentiment.

She appointed Marc Bamuthi Joseph, the center’s first-ever VP and artistic director for social impact, established the center’s first hip-hop culture program and made sure the center’s doors stayed open to artists from around the world.

“It is important to understand that artists are really the mirror to who we are as a society,” Rutter said. “The artists are truly the ones telling our stories. If we really believe in the American value of freedom of expression, artists will stand up and tell those stories.”