The subsurface ocean hidden beneath the icy shell of Saturn’s moon Enceladus harbours complex organic molecules, a new study reveals, offering compelling further evidence that the small world possesses all the right ingredients to host extraterrestrial life.

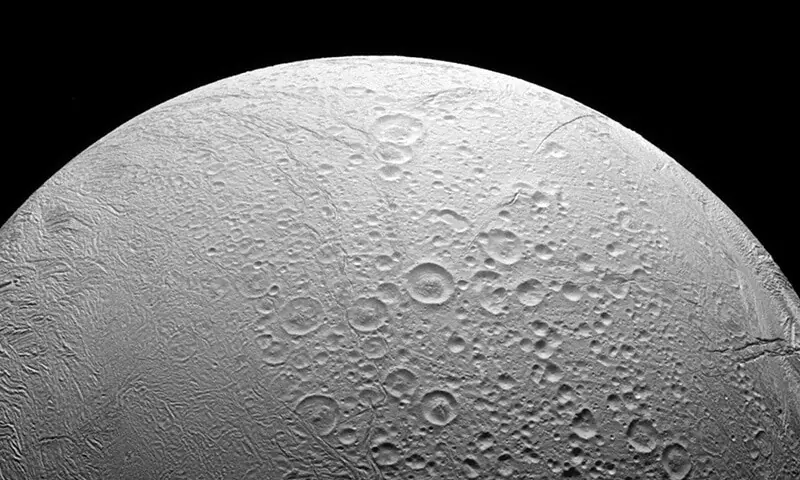

Just 500 kilometres (310 miles) wide and invisible to the naked eye, the white, scar-covered Enceladus is one of hundreds of moons orbiting the sixth planet from the Sun. For a long time, scientists believed it was simply too far from the Sun—and therefore too cold—to be habitable.

However, the Cassini space probe’s multiple flybys during its 2004–2017 mission to Saturn and its rings dramatically altered this view. The mission discovered conclusive evidence that a vast, saltwater ocean is concealed beneath the moon’s kilometres-thick layer of ice. Since then, scientists have been meticulously sifting through the data collected by Cassini, revealing that the ocean contains many elements considered vital for life, including salt, methane, carbon dioxide, and phosphorus.

A crucial breakthrough occurred when the spacecraft flew over the moon’s south pole and discovered powerful jets of water bursting through cracks on the surface. These geyser-like jets propel tiny ice particles—smaller than grains of sand—into space. While some of these ice grains fall back to the moon’s surface, others collect around one of Saturn’s outermost rings, known as the “E” ring.

Nozair Khawaja, a planetary scientist at the Free University of Berlin and the lead author of the new study, stated that when Cassini flew through Saturn’s “E” ring, it was “detecting samples from Enceladus all the time,” according to a statement from the European Space Agency (ESA).

By analysing these ring samples, scientists had previously identified numerous organic molecules, including the precursors of amino acids, which are the fundamental building blocks of life on Earth. Yet, there was a lingering doubt: could these ice grains have been chemically altered after being trapped in the ring for hundreds of years or bombarded by cosmic radiation? Scientists needed to examine fresh ice grains.

Fortunately, they had the data. In 2008, Cassini flew directly into the spray spewing from the moon’s surface. Grains of ice impacted the spacecraft’s Cosmic Dust Analyser at around 18 kilometres a second. Completing the detailed chemical analysis of these particles took years, finally culminating in the study published in the journal Nature Astronomy.

Study co-author Frank Postberg affirmed that the research proves “the complex organic molecules Cassini detected in Saturn’s ‘E’ ring are not just a product of long exposure to space, but are readily available in Enceladus’s ocean.”

Caroline Freissinet, a French astrochemist not involved in the study, told AFP that while there was “not much doubt” these molecules were in the moon’s ocean, this confirmation provides “another piece in the puzzle.” She added that this success also highlights how modern technology, such as artificial intelligence, allows scientists to perform new kinds of analysis on old data.

Ultimately, to truly understand the habitability of Enceladus, a dedicated mission would need to land near the icy geysers and collect samples directly, she noted. The European Space Agency is already studying the potential for a mission that would do just that.

After all, as the agency stated, “Enceladus ticks all the boxes to be a habitable environment that could support life.”

Khawaja concluded that “even not finding life on Enceladus would be a huge discovery, because it raises serious questions about why life is not present in such an environment when the right conditions are there.”