Benazir Bhutto: An Era, a Martyrdom, and an Orphaned Politics

By Raja Zahid Akhtar Khanzada

The anniversary of Benazir Bhutto’s assassination is not merely a date on Pakistan’s calendar. It is a wound embedded in the nation’s collective memory, one that reopens every year. It is the day when politics, ideology, sacrifice, democracy, and human dignity converge. Benazir Bhutto was not just the leader of a political party. She was an era, a metaphor, and a question that still confronts Pakistan’s conscience: what is the price of truth in the face of power.

When I was a young teenager during the Movement for the Restoration of Democracy, I witnessed daily protests against martial law. The streets echoed with slogans, batons rained down, arrests were routine, and fear loomed everywhere. I often wondered what role I could possibly play. Perhaps that question found its answer in 1982, when I formally entered journalism.

Through Abdul Sattar Bachani, I became acquainted with the influential Makhdoom family, and soon the inner workings of the Pakistan Peoples Party unfolded before my eyes: the struggles, the planning, the discreet meetings conducted in silence. I held no official position, yet I was entrusted with secrets. Once, someone suggested to Bachani that I be given a party post. He declined, saying I would serve the cause better as a journalist and should be kept separate from formal politics. And so I became a silent soldier of the Peoples Party.

I knew everything, yet my weapon was information. My role was to serve as a bridge: between workers and leadership, and at times between leadership and the establishment. Whether it was the movement of ambassadors of democracy or the stories of activists who courted arrest, my task was to mobilize public opinion through newspapers. Bachani’s trust in me, and my faith in him, became exemplary. If anyone ever expressed doubt, he would say, “You can trust Raja with your eyes closed. I guarantee him.” We shared prisons, trains, confinement, and journeys together.

I was deeply influenced first by Zulfikar Ali Bhutto and later by Benazir Bhutto because they were leaders of the people. One incident, recorded by the late Fazil Rahu himself, remains a powerful reflection of Benazir’s character. In the suffocating heat of Sukkur Jail, the jailer sent word suggesting that she be allowed a fan. Each time, she returned it, saying that if her workers did not have fans, she would not use one either. We prisoners placed blocks of ice near our doors to survive the heat. When we learned that Benazir had been brought to Sukkur Jail, we sent her a block of ice as well. She sent it back, saying that General Zia would think she had weakened, and she did not want to give him that satisfaction.

This was not merely an anecdote. It was the intellectual strength of a woman who believed in defeating dictatorship psychologically, even while imprisoned.

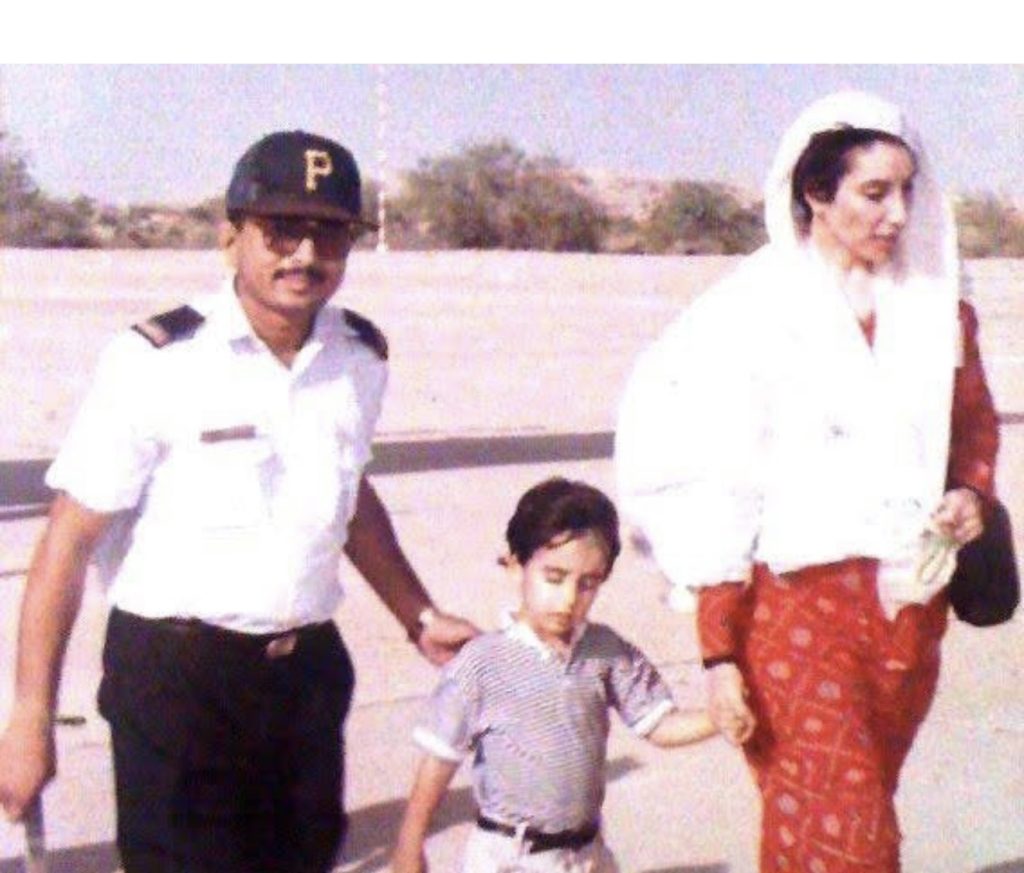

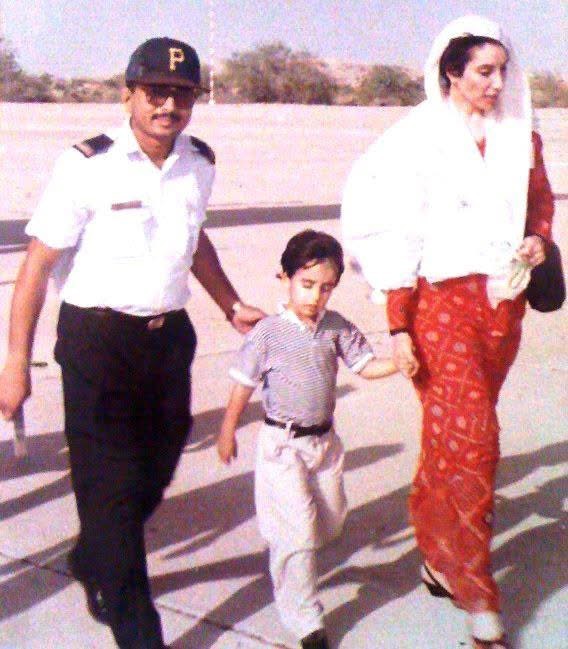

After years of struggle, when Benazir returned to Pakistan for the first time, I traveled to Lahore to welcome her. Near Minar-e-Pakistan, an ocean of people had gathered. In 1988, when her government was formed, our local MNA, Makhdoom Khaliq-uz-Zaman, helped secure me a job at Pakistan International Airlines, where I was posted to Hyderabad Airport. Even after her government was dismissed, I remained there. Whenever Benazir traveled to Larkana on Fokker flights, she passed through Hyderabad, and I greeted her each time. She always treated me with respect.

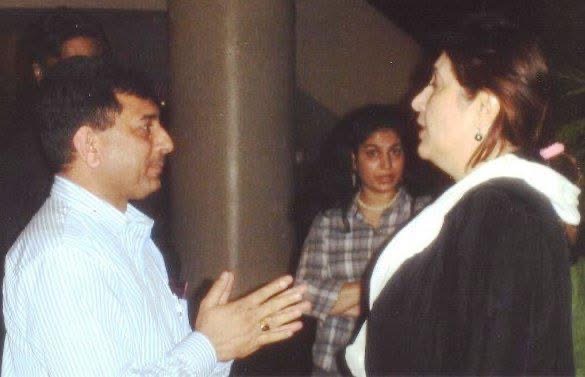

When elections approached again, as she departed from Hyderabad Airport for Larkana, I met her in the VIP lounge and recommended my late friend Abdul Latif Mangrio for a provincial assembly ticket. Sitting beside her were Qaim Ali Shah and Aftab Shaban Mirani. She asked me directly about conditions in the constituency. I told her plainly that even if the party ticket were placed on a pole, people would still vote for the party. Qaim Ali Shah observed silently, but Benazir was satisfied. The very next day, she announced Mangrio’s ticket. That was trust, more valuable than words.

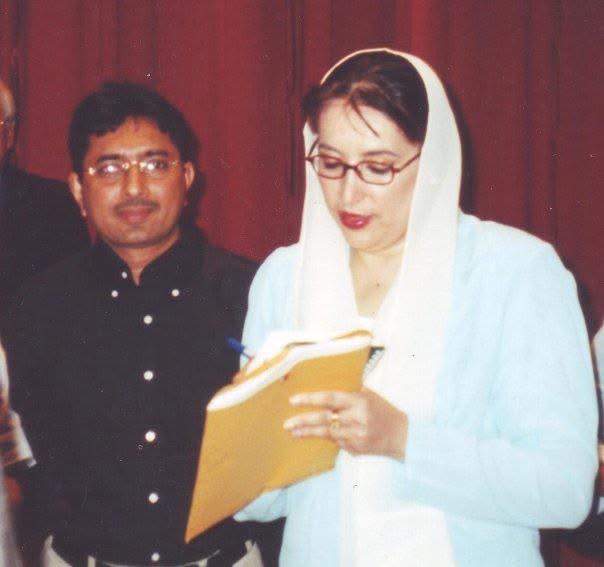

After her government was restored, we remained in contact via email. During a Sindh University convocation in Hyderabad, which she attended as prime minister, I stood at the airport amid heavy protocol. She spotted me immediately, called me over, and asked about my well-being. I was carrying a turquoise prayer bead necklace I had brought from Saudi Arabia during Umrah, hoping that one day I might give it to her. That moment arrived, and I presented it to her.

I told her that while PIA employees dismissed during the martial law era had been reinstated during her first term, 820 low-grade workers remained excluded. She immediately called Defense Minister Shaban Mirani and instructed him to summon the PIA chairman to the Governor House upon arrival in Karachi. Later, while I was speaking with Sindh Chief Minister Murad Ali Shah, an SSP rushed over and said, “Benazir is waiting for you.” She told me that I had given her a gift but asked for nothing in return. Reaching into her white gown, she gave me her own large-bead rosary and said, “This is a gift for you.” I still have it today, not as a keepsake, but as a trust.

That evening, at Governor House, she announced the reinstatement of the 820 dismissed PIA employees. These decisions were not made in files; they came from the heart.

After her second government was dismissed, I was transferred to Karachi Airport during Nawaz Sharif’s tenure. Whenever Benazir traveled, I was on her protocol duty. I never served Asif Zardari’s protocol; my loyalty was always to her. I faced threats, confrontations, hostile calls, intelligence reports, and show-cause notices from PIA. I remained steadfast, saying that if I lost the job I had taken for her cause, I would have no regret.

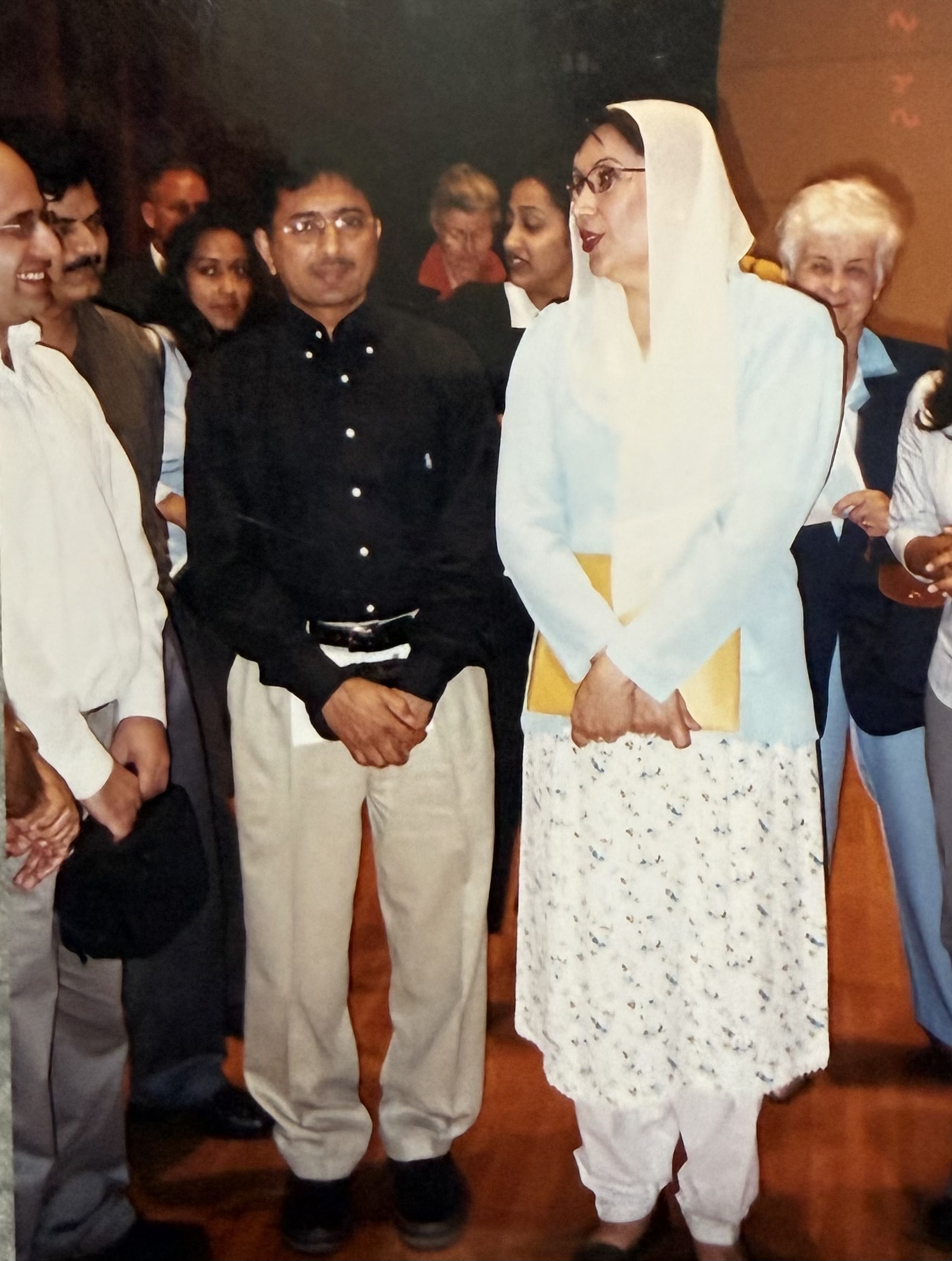

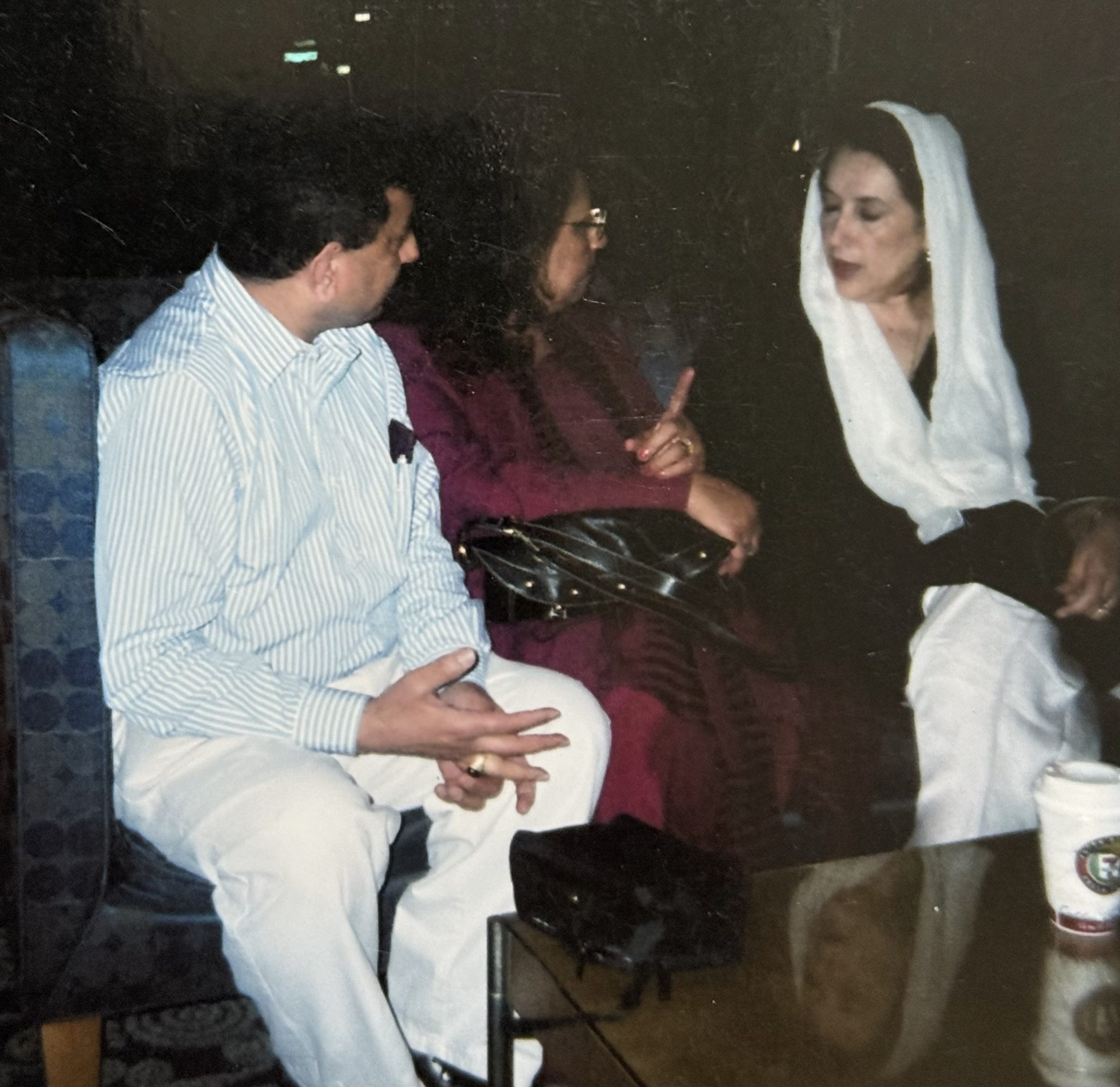

In 2000, I migrated to the United States through the visa lottery, but the connection never broke. I met her again during her lecture at Texas Christian University in Fort Worth. I later became president of the Pakistan Peoples Party Texas chapter. We organized protests against General Musharraf’s dictatorship. During her final visit to the United States, she spoke at the University of Texas at Arlington. We spent four hours together, where conversation moved beyond politics to humanity.

After 9/11, I told her the story of a Pakistani woman whose husband returned to Pakistan, leaving her alone to raise children, work twelve-hour shifts, and age prematurely. Hours later, Benazir said the story kept replaying in her mind. That single sentence captured her sensitivity and empathy. As she left, she said she would return to Pakistan to bring change.

Six months later, she did. Attacks followed, yet she stood firm. She believed the Taliban would not attack a woman. Someone had misled her. That day, she was targeted. A bullet struck her head. She was martyred.

Our home fell into mourning. Protests erupted in downtown Dallas. Slogans of “Pakistan Khappay” were raised. Power came, but so did political orphanhood. Figures like Makhdoom Amin Fahim were sidelined. Benazir’s soldiers fell silent or changed paths. I resigned from the party, but the memories never ceased.

In 2019, we organized her anniversary in Dallas through South Asia Democracy Watch and the Peoples Party Dallas chapter. Texas State Representative Terry Meza paid tribute. Kashmiri leaders, human rights advocates, and women’s rights activists attended. Senator Taj Haider and Shafqat Tanvir spoke. It reaffirmed that Benazir transcended borders.

This journey continued through confrontations with General Musharraf in Dallas, sharp questions, his admission of a deal, evasive answers, the Blackwater question, and later heated exchanges with Naeem Ashraf. These moments remain documented on YouTube. This is journalism that does not fear asking questions.

Today, the Peoples Party is confined largely to Sindh, dependent on establishment support. Bilawal, despite hope, remains constrained. If politics has become a game, it is the result of the vacuum left by Benazir Bhutto. From Liaquat Ali Khan to Zulfikar Ali Bhutto to Benazir Bhutto, those who spoke with their heads held high paid with their lives. Those who believed in compromise survived but were retired by history.

On her anniversary, I say this: Benazir Bhutto was sensitive, courageous, and placed humanity before systems. Her memory reminds us that democracy is not merely about power. It is about sacrifice, questioning authority, and the courage to understand pain. As long as this courage lives, Benazir Bhutto lives, just as her father does, forever etched in history.