At the Closed Doors of Pakistan’s Establishment, Altaf Hussain Seek Reconciliation

By Raja Zahid Akhtar Khanzada

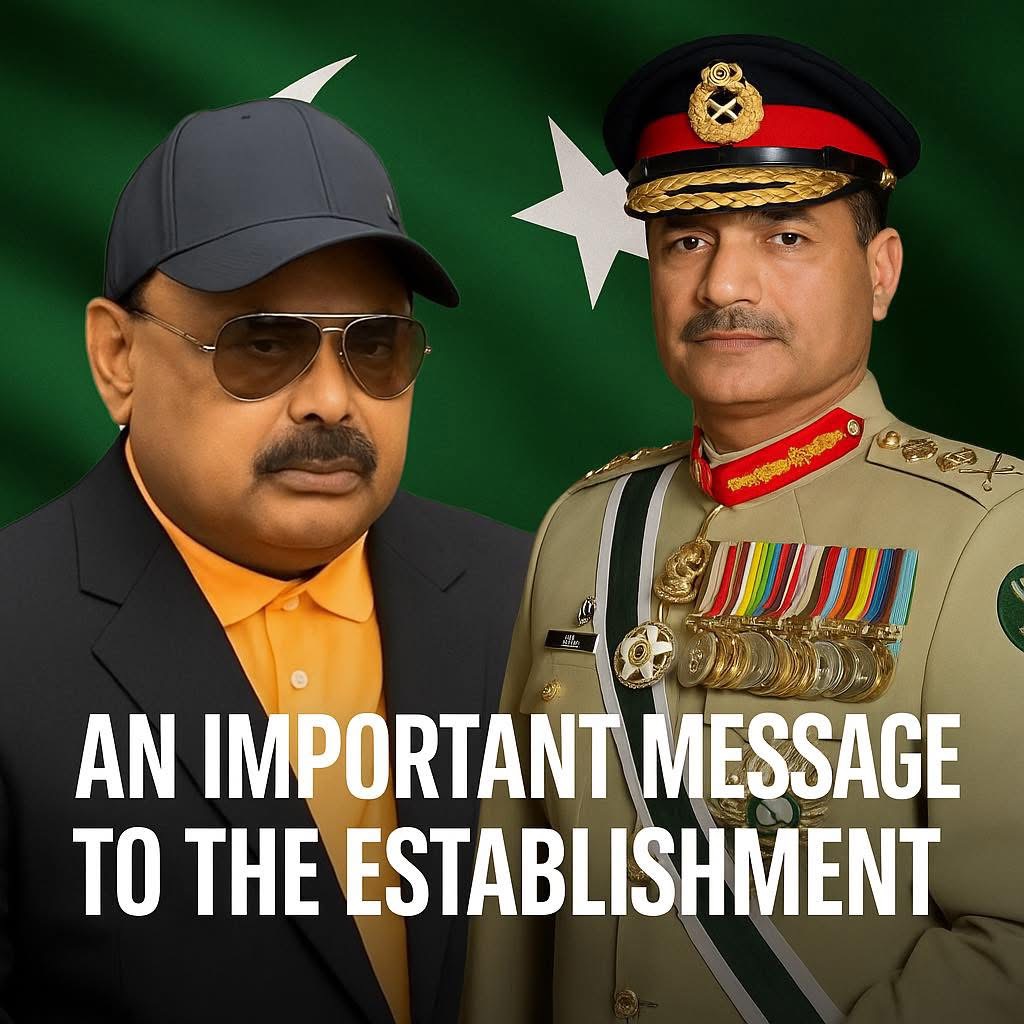

Under a dim, dust-hung sky where noise, neglect, and deprivation breathe together, a familiar voice has returned from behind the walls. Altaf Hussain, the name that once burned into the hearts of Karachi and Hyderabad’s youth as an emblem of identity, appeared two nights ago in a small TikTok frame. His words were small in format but large in consequence. The question he posed is stark: has the state forgotten this city and its people?

Echoes of reconciliation have become a recurrent sound in the corridors of the establishment. At one moment Nawaz Sharif is permitted to return home, at another the doors open to Baloch nationalist leaders, and now even the Sindh Kacha dacoits have been invited into peace arrangements. Yet the doors remain closed for the people of Karachi and Hyderabad.

If the Sindh Kacha Dacoits, outlaws whose heads carried bounties exceeding sixty million rupees, some accused of ninety-three murders, others of eighty-two, along with grave charges of kidnapping and extortion can be officially pardoned under President Zardari’s direction and the provincial cabinet’s seal, welcomed with a government “red-carpet reception,” then why not Altaf Hussain and his followers? Is this city part of another country? Are these sons of the nation unforgivable merely because they demanded their identity and their rights?

On the night of October 31, 2025, in the 340th installment of his TikTok study circle, Altaf Hussain delivered a talk that may mark the opening of a new chapter in his politics. The tone was not bitter but tempered, not combative but reflective. He said, “We have learned much from our mistakes. Now the establishment must reevaluate its policies. We are not enemies of the state. We are opponents of an outdated feudal and landlord system that runs on corruption.”

It was a tone that once roared but now swayed between contrition and hope. He did not ask for power or for money; he asked only for impartiality. If there is will, such impartiality need not be hard to provide. For the first time, anger gave way to understanding, conflict to conciliation.

This is the same man whose movement began in 1978 as the All Pakistan Muhajir Students Organization and transformed in 1984 into a political force under the banner of the Muhajir Qaumi Movement. The August 1986 rally at Nashtar Park was a turning point for Karachi politics. The movement rose on grievances over quotas and linguistic discrimination. Recall a time when MQM rallies signaled discipline, when the middle class first gained access to the levers of power, when municipal services functioned, roads were built, lights returned, and the city breathed.

Over time the movement became entangled in the same political games it once opposed. It was at times an ally of the establishment, at times its adversary. The chase for power and the fear of losing it transformed the movement’s original promise. Books in the hands of urban youth were replaced by arms, and the city was pushed into silence and terror. A gesture from Altaf Hussain could shut markets, a speech could empty Karachi streets. Thus began an era of power, politics, and fear whose echoes still haunt alleys that once bore the slogan “The Leader’s Message.”

Then the hand that once offered solace turned to operations. Factions formed, names changed. Under the banner of MQM Pakistan, many of the same faces returned to power even as their comrades had been targeted in earlier crackdowns. The city remained the same but its voices grew quiet. Those who once chanted slogans now searched for livelihoods. The young who once called themselves the leader’s soldiers now chased networks. The city has been orphaned and its silence is the most telling proof.

Meanwhile the establishment has opened doors elsewhere. Nawaz Sharif returned home under a pardon. Negotiations with Baloch leaders are underway. Reconciliation offers have been extended even to the Sindh Kacha dacoits.Yet the representative party of Karachi’s citizens stands still at the threshold.

One is reminded of Benazir Bhutto’s remark about receiving double standards because she was Sindhi. If Benazir could be treated with such divided measures, then is Altaf Hussain not also a son of this soil?

Why, then, are the doors of justice, dialogue, and pardon shut? Altaf Hussain declared, “MQM is not enemy of the country. It stands against an outdated feudal, landlord, and capitalist system.” The line introduces a new narrative in Pakistan’s political lexicon. He is not seeking confrontation with the state; he is seeking reform of the system. He says plainly that he will support whatever is necessary for Pakistan’s progress, provided impartiality and trust are granted.

That is the hinge on which this story might turn. He insisted that he does not seek the establishment’s money but only its neutrality. He asked not that his supporters be told whom to vote for or which tickets to issue. He asked for dignity and the freedom to make decisions for themselves. The tone emanated from self-respect rather than rebellion or fear, an attitude born of exile, silence, and reflection.

He also spoke of burying past bitterness without forgetting the martyrs. “What happened, we are prepared to set aside,” he said, “but we cannot forget those we lost.” The statement carries the hardness of grief but also an acknowledgment of reality. Movements cannot survive by erasing their dead, yet wisdom lies in transmuting memory into lesson rather than revenge. The Peoples Party has learned similar lessons. There is a new steadiness in his voice, as if the speaker has already made peace with himself.

He went further, saying that if the military establishment and the intelligence services take practical steps to rescue Pakistan and to reform an obsolete system, he and his followers would cooperate. It is the same Altaf Hussain who was once the establishment’s fiercest critic. Now he says, “We will not conspire against the country, nor do anything against its interest.” The change is not only in words but in outlook.

The message is in effect an invitation to the establishment to begin a conversation. The only condition is impartiality and that the people be allowed to decide their representatives. Altaf Hussain did not claim a title or demand office. He asked only for the chance to contribute what he believes he can for Pakistan. That is an appeal asking for confidence and perhaps a test as well.

History shows that when a state silences its citizens, enemies do not arrive from outside but are produced within. MQM’s politics, from any angle, remain a mirror of urban Pakistan. If the state dislikes the mirror, then it must change the face it presents, not the mirror.

It is true that MQM’s record carries dark stains, including notorious murders during the Musharraf era. Yet it is also true that at times of its ascendancy the city’s order and services improved. Today Karachi teeters under filth, unemployment, water and electricity shortages. Once it moved; now it resembles a living corpse. Altaf Hussain’s recent message is not a call to revolt nor a plea for pardon. It is a call for reform. He asks that the past be buried and the future be given a chance. If the state can treat others as it has, then Karachi should be offered the same path.

At the end, his words addressed the whole nation: “My message is for the country and for its people. For the sake of the nation I will bury bitterness and seek better relations. I hope the establishment will respond positively to my positive message.”

Those words are more than rhetoric. They are an opportunity. If the establishment allows the moment to pass, future historians will record that one person sought dialogue and the state preferred silence.

Altaf Hussain’s message is not a challenge to the establishment but a chance to repair relations with one of its citizens and to stitch together a wound years of quiet have deepened. If Punjab could welcome Nawaz Sharif home, if Balochistan could be given a language of peace, and if even the Sindh Kacha dacoits can find a path to pardon, why should the shores of Karachi remain deprived?

Perhaps the time has come for the state to unlock its closed doors, to hear the city’s heartbeat again, and to build bridges where walls now stand. Is it not time for the establishment to tear down barriers, to build bridges, and to give Altaf Hussain the same right that has been afforded to others?

For if Pakistan is to be whole, then all of us must be part of it.