The Global Table of Brutal Truth in Davos and the Future of the World and Pakistan

By Raja Zahid Akhtar Khanzada

The brutal truth is not the truth delivered in moral sermons. It is the truth placed on the table inside rooms of power, without veils and without softness. It is the truth nations prefer not to hear, yet empires are built upon it. In brutal truth, there is less hope and more reality. Principles do not speak; outcomes do. That is why, throughout history, this truth has surfaced either at moments of war or at the birth of empires. The history of the United States itself is shaped by this bitter honesty. The only difference has been in how it was spoken, some leaders concealed it, others wore it openly.

In American presidential history, Abraham Lincoln articulated this brutal truth during the Civil War when he admitted that saving the Union would require accepting moral contradictions. Theodore Roosevelt told the world that peace without power is merely an illusion. Harry Truman declared national interest without remorse after the atomic bomb. Richard Nixon acknowledged that truth does not always align with state interest. Ronald Reagan divided the world by calling the Soviet Union an evil empire. Barack Obama, behind a composed and eloquent smile, continued a silent war of drones. These were all different accents of the same brutal truth, some polished, some ruthless, all drawn from the same blade.

Donald Trump is not an anomaly in this lineage. He is simply its unmasked face. He said out loud what previous presidents whispered behind closed doors. To him, law is not a sacred text but a tool to be used. That thinking leads naturally to the old logic where power assumes the right to alter geography. His shifting positions are not contradictions but the classic language of bargaining, where pressure, threat, and concession are all components of a single deal.

With this mindset, the world has gathered around a table where peace is served on plates, yet beneath those plates lies a knife of power. The World Economic Forum in the snow-covered mountains of Davos has long been presented as a symbol of global cooperation, dialogue, and shared futures. This year, however, it revealed another reality: the global order no longer runs on trust but on pressure, interests, and balances of power.

As he left Davos, President Donald Trump remarked that it had been an incredible time. In several European capitals, that sentence sounded less like celebration and more like an alarm bell. To them, it did not mark a festival but the moment when the foundations of old alliances, built on trust, began to crack. The Greenland episode became the clearest symbol of that fracture. The narrative began in the language of ownership, shifted to military presence, then moved into economic pressure and tariff threats, and within hours transformed again into a framework where Denmark’s sovereignty remained on paper while pathways for expanded American military access quietly widened. Washington’s position was blunt: full security and full access. A Danish official noted that access already existed. Only one point was non-negotiable: Greenland would not be absorbed into the United States.

It is at this point that the familiar phrase becomes an undeniable truth: if you are not at the table, you may well be on the menu. In Davos, this ceased to be a metaphor and became a summary of contemporary diplomacy. The question is no longer about land but about rules. And when rules are defined by power, the deepest fear for small and middle powers is that decisions will be made about them, not with them.

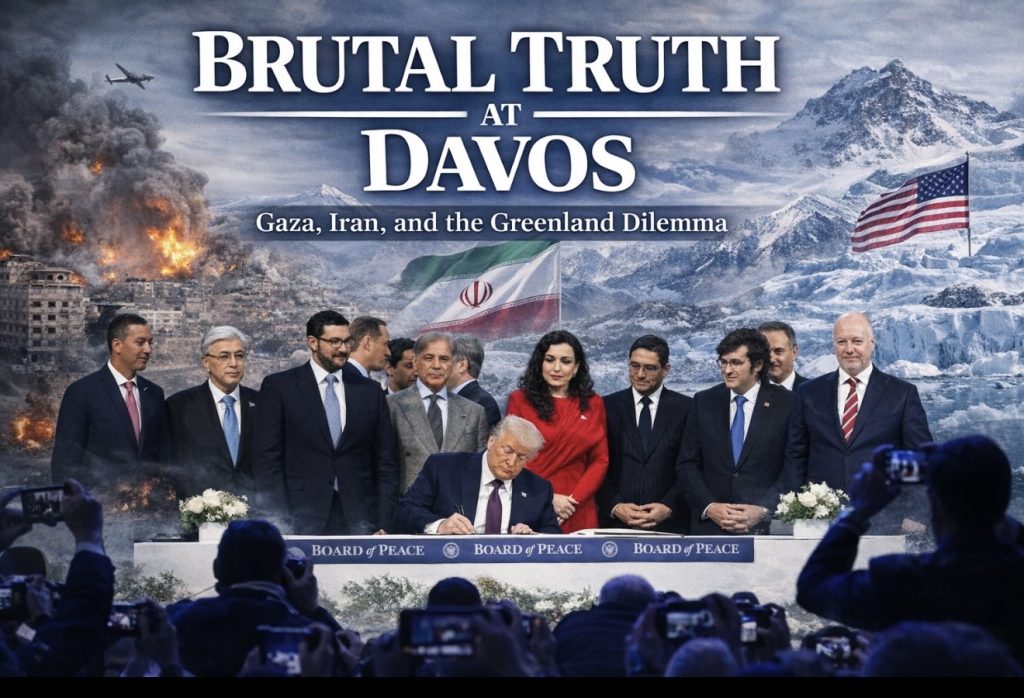

Within this environment, Trump launched his so-called Board of Peace and presented the charter signing as a new global architecture. He said it would work alongside the United Nations, yet in the same breath claimed that this board would be able to do much more. That sentence became the real alarm for critics, raising fears that the structure could undermine the centrality of the United Nations and cut through the traditional multilateral system from above.

The power logic inside this forum became clearer when reports emerged that the chairmanship could rest with Trump himself and that permanent membership might require contributions of one billion dollars each. The European Union openly questioned jurisdiction, governance, and compatibility with the UN Charter. Britain stated plainly that it would not be among the signatories. A visible wall of allies thus formed in front of the initiative.

The Gaza dimension hardened the entire picture. On the same day, Hamas reacted sharply to the inclusion of Benjamin Netanyahu, calling it a dangerous signal that contradicts principles of justice and accountability and questioning the very spirit of peace. Meanwhile, reports from Rafah, ground casualties, and the death of an infant from cold underscored the brutal distance between the glass dreams of Davos and the dust-bound reality of Gaza.

Pakistan is now seated at this same table, and this is where the analysis becomes decisive. On the surface, Pakistan’s participation offers an opportunity to remain close to global decision-making, to raise its voice alongside the Muslim world on Gaza, and to strengthen direct diplomatic channels with Washington. Yet the risks are equally visible. If this board evolves into a power-centered system parallel to the United Nations, questions will inevitably arise in Europe and other multilateral circles about where Pakistan truly stands.

These concerns echoed within Pakistan’s own Parliament. Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam leader Maulana Fazlur Rehman criticized the government for taking such decisions without parliamentary confidence and described hope for peace under Trump’s leadership as a form of self-deception. He suggested that pressure or fear may be shaping these choices and pointed out that when internal conditions include armed groups and extortion in certain regions, claims of peace abroad lose moral weight. His speech reflected a deeper reality: the state may be attempting to balance major external decisions with the management of internal political temperature, using domestic narrative strength to cushion potential diplomatic costs.

For Pakistan, the benefit lies in not being outside the room. It has secured a seat in a forum where powerful actors and major donors are in motion. This access can translate into tangible economic and political gains, particularly if Pakistan maintains a principled line on Gaza by emphasizing humanitarian aid, sustained ceasefire, and Palestinian political rights rather than reducing the issue to slogans of funding and reconstruction.

The risk emerges where this board advances with the perception of weakening the United Nations or where its decisions begin to divide allies. The most visible example so far has been Canada, whose invitation was withdrawn by Trump following a critical speech by the Canadian prime minister in Davos. The episode made clear that this platform is not only about peace but also about narrative discipline and alignment. As for Russia, the latest situation indicates that its participation is neither confirmed nor immediate, and Moscow itself has stepped back from joining at this stage. Yet even the mere association of Russia with such a forum remains sensitive for Europe. If, at any point, the platform is perceived as a pathway toward diplomatic normalization for Russia, Pakistan could face unnecessary scrutiny and narrative costs in European circles.

China’s absence sends a quiet but clear message. Beijing engages seriously only where it sees real weight in agenda-setting or at least no impression of a single capital’s project. As a major economic and supply-chain power, its absence creates a vacuum. India, meanwhile, typically chooses patience over immediate alignment. It maintains proximity with the United States, competes with China, and avoids fully severing ties with Russia. At such tables, it often remains silent to preserve maneuvering space. If Pakistan appears hastily aligned in one direction, New Delhi will seek to turn that perception to its advantage. If Pakistan speaks clearly on legal, humanitarian, and principled grounds, it becomes far harder to frame negatively.

The Muslim world’s participation remains uneven. Some offer full support, others remain cautious, and many simply seek to protect their own positions. This fragmentation weakens the weaker side in large global projects. Pakistan’s more prudent path is to help shape at least a minimal shared principled voice so that participation becomes a position rather than a photograph.

In the end, the brutal truth remains that the world no longer runs on slogans but on balance. Balance is maintained only by those who sit at every table with their sovereignty intact. Pakistan is at the table. It must now demonstrate that it is not merely present but empowered and aware. Because if you are not at the table, you may end up on the menu. And if you are at the table without a voice, you are still not fully safe. Perhaps that is the defining lesson of this era: sitting down is not enough. The real question is who you sit beside and with what weight your words are heard.

Known for his forthright journalism and incisive analysis, Khanzada has written extensively on geopolitics, diplomacy, human rights, and the concerns of overseas Pakistanis. This article has been specially translated into Spanish from his original Urdu column.