The Twenty-Seventh Amendment: A Nation Between Light and Shadow

By Raja Zahid Akhtar Khanzada

I opened my eyes in a Pakistan held tight under General Zia ul Haq’s martial law. In those years a newspaper page almost never reached the reader intact; sentences vanished into the censor’s scissors. Teachers and students disappeared into jails. Peaceful rallies were treated as crimes. For my generation, democracy was not an abstract system from a civics book. It was the sting of a whip on someone’s back, the taste of tear gas and the knowledge that a wrong slogan could cost you your future.

We grew up believing that salvation would come when the vote was respected, civilians governed and the uniform returned to the barracks and the border. Perhaps that is why my mind still resists the idea that Pakistan’s stability might now be sought through yet another constitutional amendment and yet another exalted military office.

I live in the United States today. My link to Pakistan is no longer legal or electoral; it is emotional. We were born there, formed there, scarred there. Like millions across the diaspora, I still want to see that country step out of its permanent stumble and finally stand upright.

What unsettles me is how many of my old comrades in outrage have shifted their gaze. Friends who once could not hear the word “general” without anger in their voices now speak about Field Marshal Asim Munir with something like cautious admiration. In gatherings in Dallas, Houston, New York and Washington, the question is no longer whether the army should step back from politics. The question has become whether one particular soldier, seen as personally clean and strategically firm, deserves constitutional insulation so that he can “finish the job.”

Their case is simple. Here, they say, is a man who stared India down in a brief but intense four day war, has taken a clearer line against the Taliban than his predecessors, and has reportedly moved against smuggling networks that were once considered untouchable. If such a figure exists, why not give him a clear constitutional mandate and protection so that he can act without fear of political revenge later.

Whenever I hear this, the boy who chanted against dictatorship in Zia’s Pakistan wakes up inside me. Are we repeating the same error, dressing it in more sophisticated language. Are we placing our democratic hopes once again at the feet of power, this time with better English and cleaner fonts.

Yet I cannot pretend that my own encounters with Mr. Munir have had no impact on how I think.

I have seen him three times in the past two years. The first was at a large community event in Washington, where overseas Pakistanis engaged him directly. The second was in Tampa, at another carefully choreographed gathering. The third was more revealing. Before the Tampa event, I was standing near the hotel entrance with a few friends when he unexpectedly walked out. He stopped, shook our hands and spoke with us for nearly twenty minutes.

There was no visible stiffness, no theatrical command presence. He listened without interrupting, responded in measured tones, and carried himself with the calm of someone used to decisions but wary of words. More than three years into his tenure, his name has still not been credibly linked to the land deals, secret commissions and offshore fortunes that have dogged many Pakistani officers before him.

That said, Pakistan’s structural reality cannot be sentimentalized. For decades the army chief has been the country’s unofficial sovereign. Civilian governments changed, prime ministers fell, parties rose and collapsed, but the final door of real power stayed in the same place, outside the written text of the constitution.

Supporters of the new Twenty Seventh Amendment argue that this arrangement is precisely what needs to be dragged into the light. If, in practice, major decisions on war and peace, foreign policy and internal security have long been made at General Headquarters, then writing that reality into constitutional language, they say, is not a fresh coup but a form of belated honesty. Power exists whether or not we acknowledge it. Better, in their view, to define it than to pretend it is not there.

The recent clash with India strengthened their confidence. Even some lifelong critics of the establishment concede that Pakistan’s response this time was unusually swift and psychologically sharp. At the same time, the country has had to deal with an emboldened Taliban and other militant groups along the western frontier. For years religious militancy was treated with a mix of condemnation and quiet indulgence. Certain factions were denounced in public and tolerated in private, as possible “assets” for a darker future.

It is here that another thread enters the story. A close friend of mine, a retired customs officer who spent decades on the Afghan border, describes the old ecosystem of Afghan transit trade scams, smuggling routes and informal “cuts” flowing to powerful civilians and some officers. According to him, this network was finally disturbed on Mr. Munir’s watch. Long dormant files surfaced. Some individuals, including officers, were removed. The message, my friend insists, was unmistakable: the border is not only a line on the map, it is an economic artery, and its corruption is a national security risk.

Put together, these shifts have forced even hardened skeptics to reconsider their certainties. The amendment’s backers argue that if a military leader is prepared to confront India more clearly, face down militant groups without coded ambiguity and disrupt lucrative illegal networks, then leaving him fully exposed to the next political turn would be reckless. In their telling, constitutional protection is not about appointing a new monarch. It is about creating continuity in a system that has been trapped in permanent crisis.

I remain unconvinced. I came of age believing in the 1973 Constitution and have written two long columns criticizing this amendment. Every additional legal shield granted to the military, in my view, squeezes the already shallow lungs of democracy.

And yet, in recent months, I have found myself less quick to dismiss the other side. Friends remind me of my own words: that the army chief has long been Pakistan’s de facto ruler. If the amendment merely codifies that fact, they ask, is it really a new sin or simply an uncomfortable recognition of how the state actually works.

The conversation grows sharper when the Pakistan Tehreek e Insaf comes up. It is not lost on anyone that in 2018 PTI happily rode into office on a “hybrid” arrangement: engineered alliances, a tilted media landscape, a deliberately weak civilian cabinet and a powerful military partner behind the curtain. As long as the partnership held, it was marketed as reform. Only when the same establishment shifted its support elsewhere did the system suddenly become an intolerable tyranny.

You invited the umpire to step onto the pitch, my friends say. You cannot now demand that he act like a neutral spectator sitting in the stands.

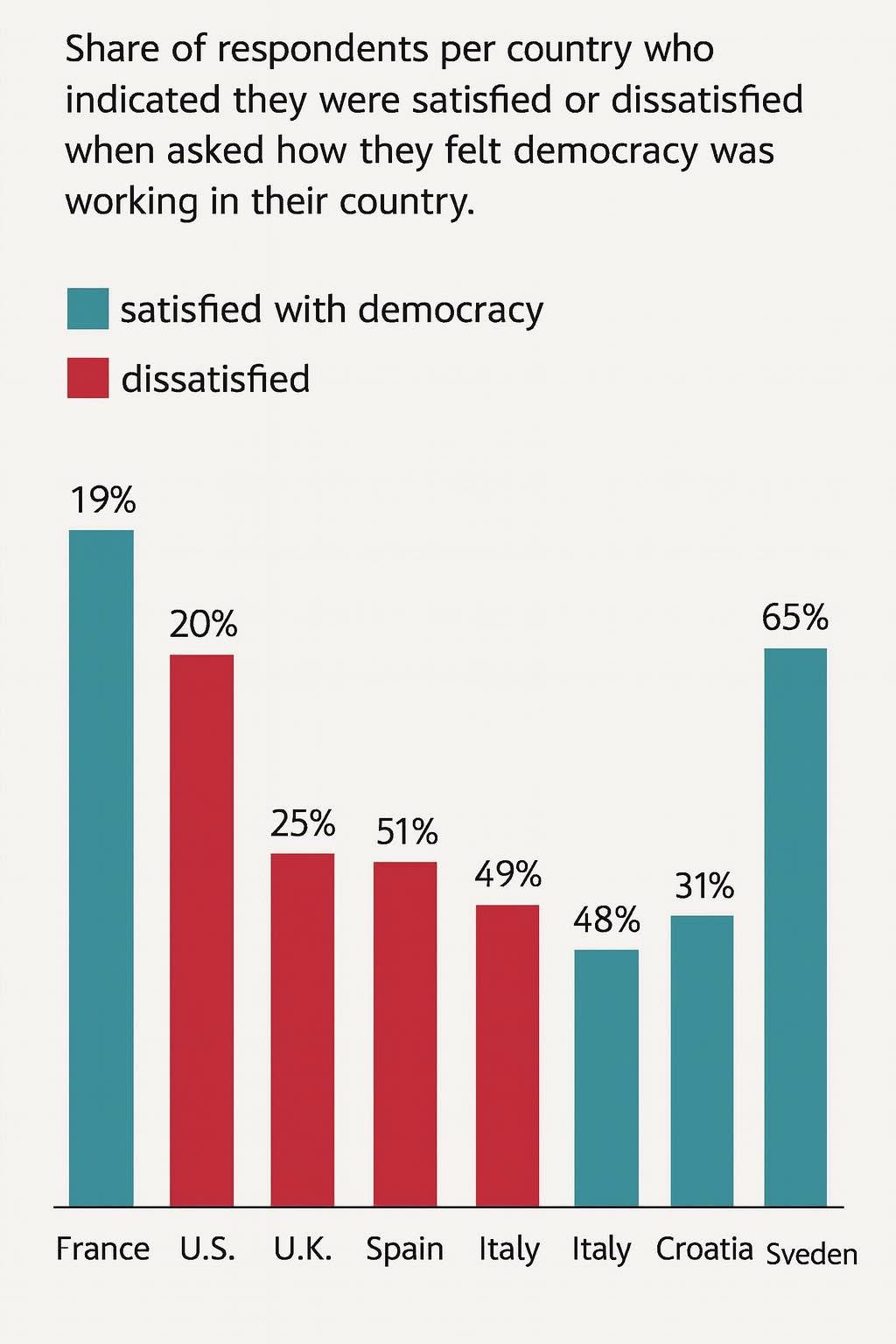

Beyond Pakistan, opinion research by firms like “IPSOS “ shows something else: a wider democratic fatigue. Across the United States and Europe, majorities still say they support democracy as a principle, but satisfaction with how it is functioning is low. Economic inequality, corrupt elites, polarizing media ecosystems and paralyzed legislatures have eroded confidence even in long established democracies.

India, often celebrated as the world’s largest democracy, has been described by several global indices as sliding toward electoral autocracy. National elections continue, but the media space is dominated by a single narrative, institutions face pressure and minorities, especially Muslims, find their breathing room shrinking. The gap between voter aspiration and state behavior is widening.

Supporters of Pakistan’s amendment look at that wider landscape and draw their own lesson. If even strong democracies are struggling to manage fragmentation, they argue, then a fragile nuclear state caught between an assertive India, a volatile Afghanistan and a shifting Iran cannot afford a scattered chain of command. They point out that India’s military strength rests on a unified command structure, and suggest that Pakistan, located at a more dangerous crossroads, needs an even clearer center of gravity.

In that framing, the Twenty Seventh Amendment does not create a new throne. It formalizes an existing structure and seeks to channel all major security decisions through one constitutional doorway instead of three competing ones.

The world’s reaction to Pakistan’s recent confrontation with India has emboldened this view. From Washington to the Gulf, foreign governments have begun to speak of Pakistan’s security apparatus with a seriousness that had faded during years of political chaos. President Donald Trump has repeatedly praised Pakistan’s “security restructuring.” Arab states have engaged Islamabad with renewed interest. For the first time in a long while, Pakistan has projected an ability to act decisively without dissolving into internal paralysis.

Whether one likes him or not, Field Marshal Munir has been central to this repositioning. In his meetings with American officials he has neither retreated nor resorted to theatrical defiance. In my own interactions with him in Washington and Tampa, I sensed both urgency and restraint: the unease of a man who knows his country is brittle, and the discipline of someone who understands how easily power can be wasted.

The amendment’s most articulate defenders insist that defining the role of a Chief of Defence Forces, clarifying military authority inside the constitution and shifting constitutional disputes from a politicized Supreme Court to a specialized court will reduce institutional chaos. For a state battered by militancy, economic fragility and polarized politics, they say, a more coherent security structure is not a luxury but a survival strategy.

I cannot deny that the logic has force. I simply worry about the price. No constitutional shield can guarantee that future field marshals will be as cautious or as personally untainted. Power, once expanded, rarely contracts voluntarily. Pakistan may be trading long term democratic breathing space for a short term sense of order.

Still, to ignore the arguments of those who support the amendment would be to write propaganda, not analysis. Nations that debate their constitutions seriously must confront the full picture: their hopes and their fears, their ideals and their realities.

The truth is that no one yet knows what this amendment will become. It may join the long list of Pakistani experiments that began with solemn declarations of necessity and ended in fresh crisis. Or, for a time, it may act as a kind of scaffolding that prevents a damaged system from collapsing entirely and buys space for economic and administrative recovery.

What worries me is less the text of any single clause and more the habits we are forming. Each time we answer political failure with a new concentration of power, we teach ourselves that democracy is an ornament, not an operating system. Each time we accept that only a soldier can steady the republic, we make it harder for civilians to ever learn how.

For now, Pakistan stands between light and shadow, searching for balance, suspended between fear of chaos and fear of control.

I stand there as well, a critic who still believes in the promise of the 1973 Constitution, but who cannot entirely ignore the hard questions raised by those who see this amendment as a necessary response to a dangerous world. I am shaped by the wounds of martial law, yet alert to the weaknesses of a democracy that has too often betrayed its own citizens.

History will take its time. It always does. Our responsibility, in this moment, is at least to think honestly, to argue in full sentences and not only in slogans. Whatever opinion we form about the Twenty Seventh Amendment, it should be formed in the light, not in the comforting darkness of our familiar certainties.