Imran Khan made the decision to roar back to power in 2022 by operating outside of the country’s mainstream political paradigm. Numerous political commentators claim that his Pakistan Tehreek-i-Insaf (PTI) party discussed facilitating an economic slide that would have resulted in an economic collapse and widespread anti-government protests, such as those in Sri Lanka in 2022.

Imran Khan and his party began to contemplate staging protests similar to those in Bangladesh that toppled Sheikh Hasina Wajid’s government after this “tactic” failed and the current coalition government, with assistance from the military establishment, was able to somewhat halt the economic decline. The “plan” as well failed.

Before this, the party made a daring attempt in May of last year to supposedly start a “mutiny” in the military against the current army chief and get other senior officers to free Khan from jail.

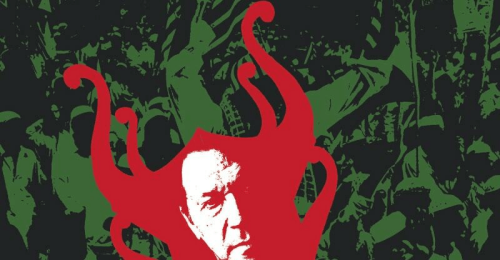

The mainstream political paradigm may be disrupted in certain ways by the nature of politics. However, it frequently fails to demolish it. Khan, his supporters, as well as some activist lawyers and “independent” journalists who have chosen to side with him, viewed Khan’s attempt to storm the paradigm from the outside as a “revolutionary” act.

The Pakistan Tehreek-i-Insaf’s political anarchy and emotional brand is an attempt to barnstorm the mainstream political arena from the outside. But can rhetorical politics like this last for a long time?

Therefore, it is not surprising that these individuals frequently used the term “revolution.” If Khan was not released from jail, they issued a warning that a civil war would break out in the nation. Interestingly, however, Khan’s newfound “anti-establishment” admirers are aware that he will immediately abandon his anti-establishment rhetoric if he can reach an agreement with the establishment.

I was recently informed by a leftist activist that their support for Khan is a “tactical maneuver” to oust the “establishment” from politics by joining the “anti-establishment” bandwagon, which the PTI began to build after Khan broke up with his former military supporters. All of Khan’s backers, as well as his newfound admirers among activists, are attempting to disrupt mainstream politics from the outside. Political scientists refer to this behavior as “anti-politics.”

This term has the immediate connotation of total political distance. However, the majority of the time, it is used to describe a political subfield that operates outside of conventional political thought. After gaining control of the paradigm, its goal is to dislodge and destroy it. As a result, in this context, “anti-politics” refers to a reaction against mainstream politics, which is perceived as “corrupt,” static, and biased in favor of “political elites.”

Even though its goal is to invade the mainstream political paradigm, evict those who are rooted in the paradigm’s workings, and establish those exhibiting “anti-politics” as the paradigm’s new wielders of power, its view of mainstream politics is anarchic and “anti-establishment.” This does not always necessitate widespread civil unrest. Since the beginning of the 2010s, “anti-politics” as a populist strategy has successfully used democratic means to gain mainstream political power.

Because of this, the term “anti-politics” is frequently associated with populist groups that savagely target established political figures and government agencies. Populists amplify and bolster any society-wide “anti-politics” sentiment. When in reality, it is just another means of acquiring conventional power, coming to power in this manner is portrayed as a moral and revolutionary act.

However, proponents of “anti-politics” fail to consolidate their position because their disposition prevents them from utilizing the tools required to remain in power—or tools that they detest and wish to destroy—even when they do break the mainstream paradigm of politics. Khan is only one illustration of this. Not only did he struggle to maintain power by attempting to destroy what a populist like him detested, but he also felt isolated and helpless after his ouster when he wanted to rejoin the established order from the outside.

When used to breach the mainstream political paradigm, “anti-politics” can only produce brief bursts of emotion and commotion; however, these only last so long because mainstream politics has powerful tools at its disposal to maintain its influence, repel outside attacks, and quickly repair itself. As a result, anti-politics is left with nothing but meaningless accolades to romanticize itself, such as “heroic,” “idealistic,” “brave,” and so on. When this strand of politics does gain power, it either loses it quickly or completely eludes it.

But why has there been an increase in “anti-politics” over the past ten years? An intriguing response is provided by political scientist Manuel Anselmi and sociologist Paul Blokker. They attribute the problem to societies’ depoliticization beginning in the 1980s. The majority of nations adopted neoliberalism as a political philosophy and economic model beginning in the 1980s.

The goal of neoliberalism was to establish a globalized economy governed by the private sector and free from state and government control. Governance was outsourced to “technocrats” and the economy was outsourced to large corporations and banks by governments. State authority and responsibilities diminished. Additionally, neoliberalism discouraged active political engagement. Depoliticization was the result of this.

After the global financial crisis of 2008, neoliberalism began to be criticized. Those affected by it started to seriously censure the confidential area and the legislatures who were blamed for safeguarding it. The backlash sought either something “new” or a return to a wild-imagined “pristine” past. The recession was met with a sharp criticism. Other than rhetorical flourishes about purifying the system, it offered no actual alternatives.

A whole generation had left politics after depoliticization. Therefore, the politics that were brought about by the recession were rhetorical, utopian, emotional, and naive. “Anti-politics” was the term. Populists took advantage of this. Even though it was “anti-politics,” neoliberalism successfully manipulated mainstream politics by forming amoral political and economic alliances.