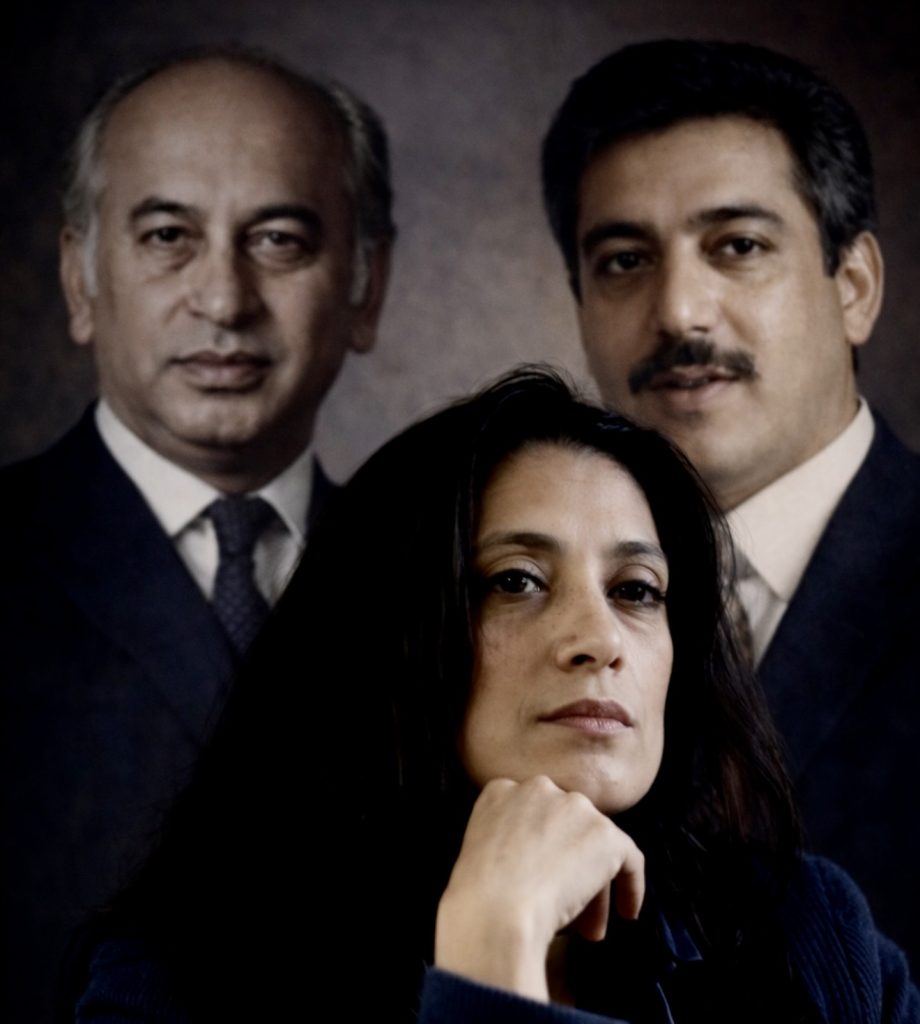

Fatima Bhutto, a Quiet Reckoning With Love, Power, and the Shadow of a Political Dynasty

By Raja Zahid Akhtar Khanzada

My first encounter with Fatima Bhutto did not take place at a literary festival, a book launch, or an international forum. I saw her for the first time much earlier, during political tours across Sindh that preceded her father’s arrival, when she would accompany her mother, Ghinwa Bhutto. She was still an adolescent then, often carrying her infant brother, Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto Jr., in her arms. The political atmosphere of Tando Allahyar from that period remains vivid in my memory. It was the time when Abdul Ghani Dars, after breaking away from the Pakistan Peoples Party, joined the PPP Shaheed Bhutto, a development that dominated political discussion at the time. It was in that charged environment, moving with that political caravan, that I first saw Fatima Bhutto at Abdul Ghani Dars’s residence in Tando Allahyar. At that moment, I could not have known that behind her quiet face lay a life whose wounds would surface decades later, not as slogans, but as words.

Fatima Bhutto is the granddaughter of Shaheed Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, Pakistan’s most powerful, controversial, and ultimately decisive prime minister. The Bhutto name has become synonymous with political power in Pakistan: mass popularity, party machinery, influence within the state structure, and international recognition. Yet attached to that same name is a long ledger of sacrifice that cannot be separated from Pakistan’s political history. Zulfikar Ali Bhutto’s execution, the mysterious killing of his younger son Shah Nawaz Bhutto, the assassination of Mir Murtaza Bhutto—Fatima Bhutto’s father—while Benazir Bhutto was prime minister, and finally Benazir Bhutto’s own assassination. These are not merely historical events; they represent the price paid by one family, a cost etched deeply into the national conscience.

Today, the third generation of that lineage stands before us. On one side are Bilawal Bhutto Zardari and Asifa Bhutto. Yet the principal political beneficiaries of these sacrifices have been Benazir Bhutto’s husband, Asif Ali Zardari, and his sister, Faryal Talpur. Under the banner of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto’s name, they not only secured political power and control of the party but also expanded their wealth and influence. On the other side of this same third generation stand Fatima Bhutto and Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto Jr. There was a time when speculation suggested that Fatima Bhutto might enter active politics, but she consciously chose to step away from that path. Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto Jr., her half-brother, has now entered politics, yet he has not achieved the position or authority that the family name might suggest, despite the fact that a large segment of Sindh’s population continues to regard the Bhuttos as political saints. The reason for this divide lies in control—control of the party and organizational power—which propelled one faction to the center of authority while relegating the other to the margins. It is against this backdrop that Fatima Bhutto emerges, through her recent interview, on an entirely different front. This is a battle not fought in rallies or courtrooms, but within the self—within trust, within endurance, and within silence.

Fatima Bhutto’s recent interview in The Guardian appears, on the surface, to introduce her forthcoming memoir, The Hour of the Wolf, a phrase she renders as “the moments of silent suffering.” In truth, however, it is a profound and painful confession. The metaphor of the wolf in The Hour of the Wolf is not merely a reference to a wild animal; it points to the darker aspects of human and state instinct—the capacity to devour one’s own relationships, and even one’s own people, in the pursuit of power, fear, and control. According to folklore, during harsh winters when prey becomes scarce, a starving wolf waits for weakness within its own pack. When one falters and collapses, the pack turns on it, consuming one of its own to survive. That moment is the essence of the metaphor: danger born not from outside, but from within, where survival demands sacrifice of the familiar.

In Fatima Bhutto’s account, oppression does not arrive at the hands of a stranger. It comes from the very person who is named love, trust, and intimacy. The most dangerous moment, she suggests, is when violence does not strike from without, but is born within relationships, cloaked in claims of care and protection. This is the hour when the wolf goes hungry, and love slowly transforms into prey.

At its core, this is the story of a woman’s scream that does not echo loudly, but instead settles quietly into the bones.

Fatima Bhutto speaks of a long relationship—nearly eleven years—that revolved around her life. She does not name the man involved; she refers to him only as “The Man.” This anonymity is itself symbolic. Oppression, she implies, often operates without names.

She explains that she did not want to tell this story. There was shame, hesitation, and deep internal resistance. But she ultimately chose to reveal her personal truth in the hope that it might help other women who experience betrayal and emotional abuse in the name of love. Her words suggest a quiet wish: that had someone else written such truths earlier, she herself might have found guidance, a map through pain.

From this point onward, her story ceases to be merely a confession and becomes a document. In the family she comes from, fear and vigilance were part of daily life. She recalls being trained from childhood to keep a bag packed, to speak cautiously on the phone, to never disclose her location, to treat secrecy as survival. Under the shadow of politics, such training creates resilience, but it also cultivates silence. When secrecy becomes habitual, one can lose the ability to distinguish between silence that protects and silence that enables harm.

Fatima Bhutto reveals another layer of her life. Her parents divorced when she was young, and she went on to live with her father and her stepmother, Ghinwa Bhutto. At the age of fourteen, her father was assassinated. Such a trauma leaves lasting marks on any child’s psyche: insecurity, an uncertain future, and a persistent, unnamed fear. She says she received immense love from her father, but the absence of shared parental affection and the instability of her childhood left a void—one that the wrong people can exploit.

It is within this context that she describes her failed love. An eleven-year relationship in which they met only once a month, as her life was consumed by work and obligations. She recounts being humiliated in restaurants, shopping centers, and public spaces, enduring degradation in the name of love. The most piercing moment in her testimony is a statement that both fractures and heals:

“ He harmed me deeply, but he did not break me. I was strong—and that strength came from my father, Mir Murtaza Bhutto.”

At first glance, it reads as a declaration of resilience. Yet beneath it lies an admission that strength does not always protect. Sometimes, strength becomes a dangerous illusion—the belief that one can endure anything—which in turn makes endurance easier for the abuser. Fatima Bhutto’s story dismantles the myth that only weak women are exploited. It shows that intelligent, worldly, and aware women can also remain silent for years, especially when they have been conditioned to believe that silence equals survival.

She notes that as time passed, her age advanced, yet the man remained unwilling to marry. Fear took hold—that she might lose the chance to become a mother. In response, she underwent fertility preservation in France, safeguarding the possibility of motherhood. This was not merely a medical decision, but a psychological one. Prolonged uncertainty compels women to make even the most intimate choices under the shadow of fear.

In 2021, Fatima Bhutto ended the relationship and chose to begin anew. She later married and, within a short span, became the mother of two children. There is no cinematic resolution here—only a quiet truth. Life is not a closed door. Even a delayed but correct decision can alter its course.

The interview also reveals another dimension of Fatima Bhutto. She speaks of Gaza—of her own safe surroundings, and of women giving birth under bombardment. In that moment, she transcends the personal and becomes a moral witness. Whether oppression is personal or state-driven, she suggests, its psychology is often the same: control, enforced silence, and the shaming of those who speak.

If there is one lesson to draw from this interview, it is that silence is not always dignity. Sometimes, silence is simply old conditioning. And breaking that conditioning is the first act of freedom. Fatima Bhutto does not curse politics, but she dismantles the silences cultivated under its shadow. That is the true significance of this essay.

It is also where the pain of the Bhutto family’s third generation converges with the sacrifices of the second. On one side are stories of power; on the other, stories of cost. Between them stands a woman’s private truth—one that could become a lamp for thousands of others, if only we listen with seriousness, refuse to reduce it to gossip, and learn to measure love not by intensity, but by peace.

Known for his forthright journalism and incisive analysis, Khanzada has written extensively on geopolitics, diplomacy, human rights, and the concerns of overseas Pakistanis. This article has been specially translated into Spanish from his original Urdu column.